July 23, 2014

Finding the Genes Behind Smiles: Lifelong Advocate of Cleft Prevention Spreads Word About Research

Dr. Marie M. Tolarova established the craniofacial genetics research and cleft prevention program at University of the Pacific’s Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in 2000 with her husband and scientific collaborator Dr. Miroslav Tolar, an associate professor of orthodontics and biomedical sciences, and head of Pacific Regenerative Dentistry Laboratory at the Dugoni School of Dentistry.

A University of the Pacific orthodontics professor known by her colleagues as the “grandma of cleft prevention” is leading one of the world’s largest studies into the genetic causes of cleft lip and palate, work that is pointing the way to effective strategies to prevent the disfiguring disorder.

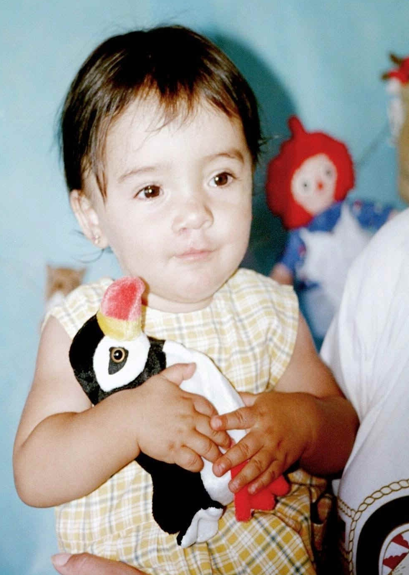

Marie M. Tolarova heads the Craniofacial Genetics Lab at Pacific’s Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco, where she oversees the only cleft prevention research program in the country. She and her team are searching for genes and nongenetic factors, such as nutrients, associated with cleft lip and palate.

Among genes Tolarova’s team has been studying for several years, one gene in particular when mutated can compromise an individual’s ability to metabolize folic acid by 50 percent. The mutation may have a devastating effect on embryos if women who carry this mutation don’t compensate with supplemental folic acid.

Born in 1942 in Tabor, Czechoslovakia, Tolarova is a physician board-certified in both pediatrics and medical genetics. When she began her career as a pediatrician, she was troubled by the families of children she saw with craniofacial abnormalities such as cleft lip and palate. “The mothers would ask me, over and over, ‘What did I do wrong?'” said Tolarova. “I began to wonder what we could do to prevent clefts from happening.”

Tolarova first published research on cleft prevention three decades ago in the British medical journal The Lancet, suggesting that many familial cases of cleft lip and palate could be prevented by high doses of folic acid and multivitamins before conception and in the beginning of pregnancy.

Her work has continued at Pacific, where the orthodontic program is the only one in the country in which residents can participate in surgical cleft medical missions to developing countries. Through Rotaplast International, a charitable organization sponsored by Rotary International clubs, residents join a multidisciplinary team providing dental and orthodontic care. They also collect data and specimens for research.

In the past 13 years, Pacific faculty and orthodontic residents have gone on 81 Rotaplast cleft missions to 20 different countries, and Tolarova herself has participated in 50 of them. She said the value of professional services donated on these trips amounts to more than $2 million.

Through these trips, Tolarova’s lab has collected genetic information that helps researchers understand causes of cleft lip and palate, and allows them to make recommendations for prevention in different communities.

“We have found, for example, that in Guatemala, there is a much higher occurrence of mutations of folate-related genes in patients with a cleft and among their relatives compared to those with no cleft,” said Tolarova. “So, we encourage health professionals to recommend folic acid supplements to women planning pregnancy, especially to those at high risk of having a baby with a cleft, as well as genetic evaluation and counseling.”

Tolarova said that the lifetime medical cost to treat a child born with cleft lip and palate is conservatively about $100,000, so funding prevention is clearly good health policy. But for Tolarova, cleft prevention is about the families. “This is my lifetime passion,” she said. “I believe we can save children, we can save their smiles.”

While Tolarova has been invited to speak about her work in Dubai, the Republic of the Maldives, and India over the past year, she dreams about expanding her work closer to home.

Orofacial clefts are one of the most common types of birth defects in the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC estimates that about 2,650 babies are born with a cleft palate in this country each year and 4,440 babies are born with a cleft lip with or without a cleft palate.

“I would love to get the funding for Pacific to provide clinical care to patients with cleft lip and palate,” she said. “We have exceptional, unique data and specimens, and we should use it not only for research, but for what dentistry does best: preventive care.”

Tolarova established the craniofacial genetics research and cleft prevention program at Pacific in 2000 with her husband and scientific collaborator Dr. Miroslav Tolar, an associate professor of orthodontics and biomedical sciences, and head of Pacific Regenerative Dentistry Laboratory at the Dugoni School of Dentistry.

Originally published by University of the Pacific.

Back to All Media